There’s a chance you’ve read Getting Things Done — a great book which at its core describes a system to externalise ‘to do’ items, taking them from being in your head to being written down somewhere, allowing you not to worry about them until it’s time to take action.

I read the book a while ago and found the system interesting, but never managed to implement it because of practical reasons — while the book describes a system, it doesn’t provide a tool. I tried several tools including a physical notepad (great when you have it with you, useless when you don’t) and web services such as Trello (a good tool for collaborating on a project and capturing its state, but not for lists with several layers of depth) and Google Keep (useful for searchable notes and reminders, but not for long lists or keeping track of projects). None of them were good enough for me to be able to implement the system and reap any of its benefits, and I was left having to keep things in my head.

Just a few weeks ago my interest in the GTD system was rekindled when I came across an article called “GTD in 15 minutes — A Pragmatic Guide to Getting Things Done”. I decided to give it another go using Workflowy, a list keeping service which I had previously discarded because of its (at the time) limited mobile app. I found that this was not the case anymore: the mobile app now has a great range of features including offline support, meaning that you can check and update items even when you don’t have internet access. It also supports unlimited (as far as I can tell) list depth, hashtags, dragging and dropping items between lists, and makes it very easy to add new items or mark things as done.

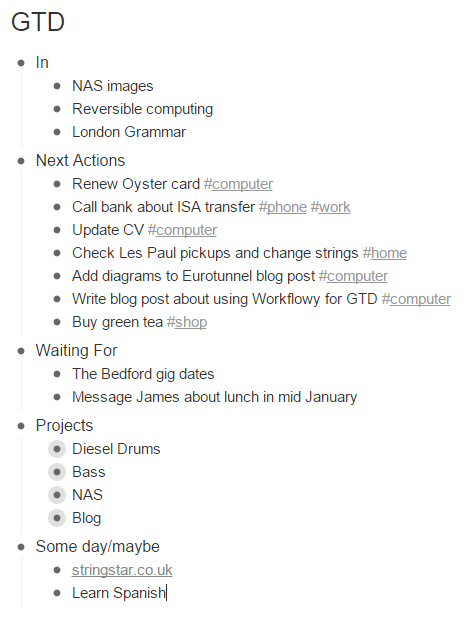

I read through the 15 minute guide and set about implementing the system in Workflowy. Here are the key things if you want to try it yourself.

Create a Next Actions list

The core insight of the GTD system is that many ‘to-do’ lists contain items that aren’t immediately doable, so they end up getting postponed indefinitely. This might be because they’re too vague (‘exercise’), too large (‘start food blog’), or both. The Next Actions list is David Allen’s proposed solution to this. This list is only allowed to contain items which start with verbs, have no outstanding dependencies, and can be started immediately.

How is this so different from a normal to-do list? The difference is that you can glance at your Next Actions list whenever you have time, pick something, and do it. It becomes a more mechanical process, and removing ambiguity surrounding a task means less chance of getting distracted (I’ve certainly had my fair share of start task -> get confused -> watch tv -> feel guilty and look for another task to start -> repeat process).

How does this system help me keep my list actionable? By having an easy-to-follow structure. New items coming in don’t get added straight to the Next Actions list if they don’t satisfy the criteria, but are added to a temporary In list and processed when convenient. There’s also a Waiting For list for items which have been delegated or have dependencies, and a Projects list for a more high level view. Lastly there’s a list of things you’ll get around to… Someday/Maybe.

Create the other lists and add some items

Here’s a more detailed description of each list. Take a few minutes here and try to come up with two or three items to add to each list. Feel free to use my list above for inspiration.

- Next Actions: a list of actionable tasks. These are all things that can be picked up by you and worked on given the right context (more on this later), and can include items like “call mum” or “buy bananas”. All of these should start with a verb, and not require input from anyone else to get you started.

- In: this is where you jot down anything that occurs to you that you want to follow up on, which as the article mentions can be anything including “your boss telling you to bake her a carrot cake, or seeing a poster for a circus you want to see.” This provides a brain dump that can be processed at a later time into items to go into the other lists.

- Waiting For: items you’ve delegated or can’t take action on right now, for example when you’re waiting for feedback from someone, or you’re planning on buying tickets for a festival once they go on sale.

- Projects: high level list of things you’re working on. Each of these projects can have one or multiple items associated with it in the Next Actions list. This allows you to keep track of the overarching goals behind items in other lists and come up with new Next Actions.

- Someday/Maybe: this might be the most important list of all, at least according to Warren Buffett. These are things you’d like to work on but not right now, and by putting them in this list you can free your mind from thinking about them and come back when you have time.

Maintain the lists

- All new items will usually be added to the In list first.

- The In and Waiting For lists should be reviewed regularly and actionable items added to the Next Actions list (unless they would take less than 2 minutes, in which case you should do them immediately).

- The Projects and Someday/Maybe lists can be reviewed less frequently to check that each active project has a next action defined.

- The Next Actions list will need to be reviewed continually — whenever you have some time, look through this list and find something you can do. This is where contexts come in.

Contexts are environments associated with certain actions. For example, the ‘buy bananas’ action can be done when at a shop, whereas the ‘fix door handle’ action requires you to be at home and ‘buy festival tickets’ is easiest when at a computer. Workflowy has a great feature for this: by using hashtags (e.g. #shop, #home, or #computer) you can tag each action with one or more contexts, and when you find yourself idle in that context you can display all the items with that tag.

While this gives you enough to get started, in the interest of brevity I’ve skipped over a lot of things which are covered in this 15 minute guide and in more depth in the Getting Things Done book. I would really recommend reading at least the 15 minute guide if you want to use this system, as you’ll win this time back in less than a few days of using it.

Sign up for Workflowy for free and get double the list capacity! This link will give you 500 free items/month, as opposed to the 250 you’d get if you signed up through their website without a referral.

If you liked this article, I would really appreciate if you could share/recommend it and check out some of my other articles below!